§ 2.2 - Best Practical Usage§ 2.2.1 - From the Command LineYou can use the command line tool in the aa_macro repo:

§ 2.2.2 - From PythonUsing (and re-using) class macro() flexibly in the context of Python 3 itself is pretty much a doddle:

from aa_macrov3 import *

mod = macro()

inputtext = '[i print some content from here][local foo bar]'

outputext = mod.do(inputtext)

print(outputtext)

inputtext = "[b more content] [v foo]" # as we're using the same object, anything...

outputext = mod.do(inputtext) # ...set up in it is still in context here

print(outputtext)

This is the result of the above Python 3 code: <i>print some content from here</i> <b>more content</b> bar That's it. There's a little bit you can do with parameters to the macro() invocation, and there are some very useful utilities within the class for insecure environments (in particular, the sanitize() and chaterize() methods), but generally, the above is all you need. There's a more concise way of doing the whole thing, too:

from aa_macrov3 import *

print(macro('[i some content]\n[i more content]'))

The downside of the latter approach is because it does not result in a reusable instantiation of the class, global and local contexts within the inputtext become essentially the same, which is not nearly as useful for many types of multi-page documents. However, for typical single page documents, this is all you need. The reason the above works just like that is because the class __str__ method returns the most recent output text generated by object.do() Then print knows enough to use that when the object is thrown in its face, so to speak. But not everything in Python 3 is so smart. For instance, this won't work...

print('This is ' + macro('[i some interesting content]') + " right here")

...because the + operator implementation for strings doesn't know enough to go grab a string method of an object. It's trivial to work around, though...

print('This is ' + str(macro('[i some interesting content]')) + " right here")

...and in fact, that form will work everywhere, including with print...

print(str(macro('[i some interesting content]')))

...so perhaps that's the best way to approach it. I'm unclear on why Python 3's + operator doesn't look for the __str__ method when it already knows it is concatenating a string, but... that's how it works. § 2.2.3 - As an Online Text Processoraa_macrov3 can provide a great styling environment for chats and commenting systems. However: You really don't want to expose aa_macrov3's built-in command functionality to the world. Trust me on this. So, in the styled chat and commenting use cases, the idea is to prevent unwanted characters from reaching the macro processor so as to maintain control of the user's input to enhance security. This is easily done with one function call to aa_macrov3, chaterize() , but let's walk through what needs to be done so you understand the process. First, we replace semicolons as part of preventing style injection; this has to be done first because everything else involves adding legitimate semicolons to the text being processed:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace(';',';')

Next by converting [ and ] to the character entities &lb; and &rb; before the text to be processed is passed along:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace('[','&lb;')

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace(']','&rb;')

Then do the same thing to angle brackets to prevent embedded scripting and other HTML trickery:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace('<','<')

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace('>','>')

To ticks (the apostrophe), to prevent SQL injections:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace("'",''')

To double quotes (the " character), to prevent other string injections:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace('"','"')

To the backslash to prevent Unicode and other raw injections:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace("\\",'\')

To colons, also to prevent style injection:

texttoprocess = texttoprocess.replace(':',':')

And then:

processedtext = macro(texttoprocess)

Or, you can have aa_macrov3 do all that for you:

texttoprocess = chaterize(texttoprocess)

processedtext = macro(texttoprocess)

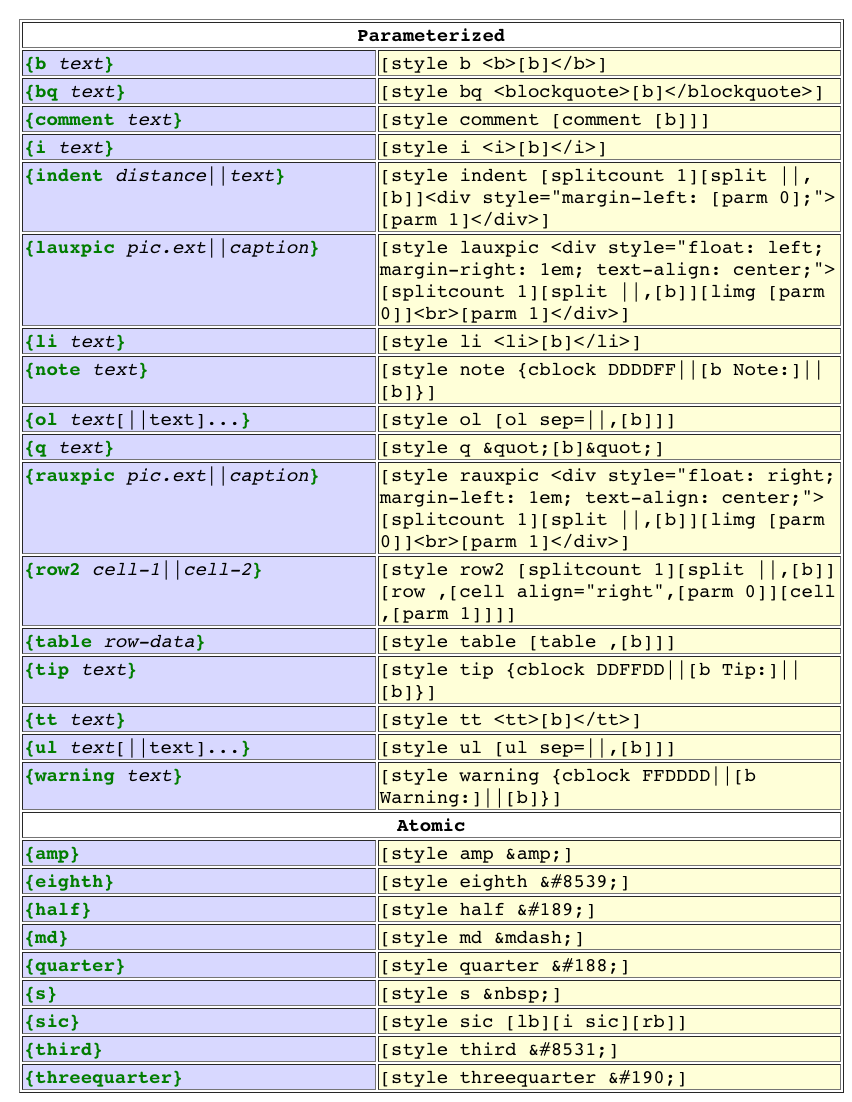

So what you have then is a circumstance where only styles can be processed. So you prepare a set of styles easily used by yourself, or guests, which are known to be safe, yet powerful and convenient. For instance, these are some of the safe styles I use in my online image gallery when I write image commentary: § 2.2.4 - Testing for Bracing Errorsaa_macrov3, because its statement boundaries are defined by bracing, not lines of text, shares a programming pitfall with LISP: if your bracing is in error in any way, problems will arise and they may not be at all what you would expect, because later language statements become improperly nested within the overall bracing environment. To assist you in staying clear of this, aa_macrov3 provides a utility function: bracecheck() You should use this whenever you save aa_macrov3 source code, assuming you aren't in the middle of writing a style or a macro and breaking for lunch or similar. Here's the basic idea; you would call bracetester() with your updated aa_macrov3 source code:

from aa_macrov3 import *

def bracetester(source):

"""Input: aa_macro source; Output: Diagnostic information."""

try:

mod = macro()

status,message,lastbalance,lastline = mod.bracecheck(source)

if status == False:

return(f'{message}last balance at line {lastbalance} with {lastline}\n')

return('OK\n')

except Exception as e:

return(e)

I embrace this in my dogfooding. For instance, wtfm uses this capability to check global styles and variables, project styles and variables, page locals and variables, and page content, each time any of them are saved.

Keyboard Navigation

, Previous Page . Next Page t TOC i Index on February 18th, 2026 at 12:52 MT |